Omega-3 fats and your heart

There's yet more evidence about the health benefits of these polyunsaturated fats — and they don't necessarily have to come from fish.

Since the late 1970s, hundreds of studies have supported a link between omega-3 fatty acids in the diet and a lower rate of heart attacks and related problems. The best-known omega-3s — found mainly in fatty fish such as salmon, herring, and mackerel — are eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

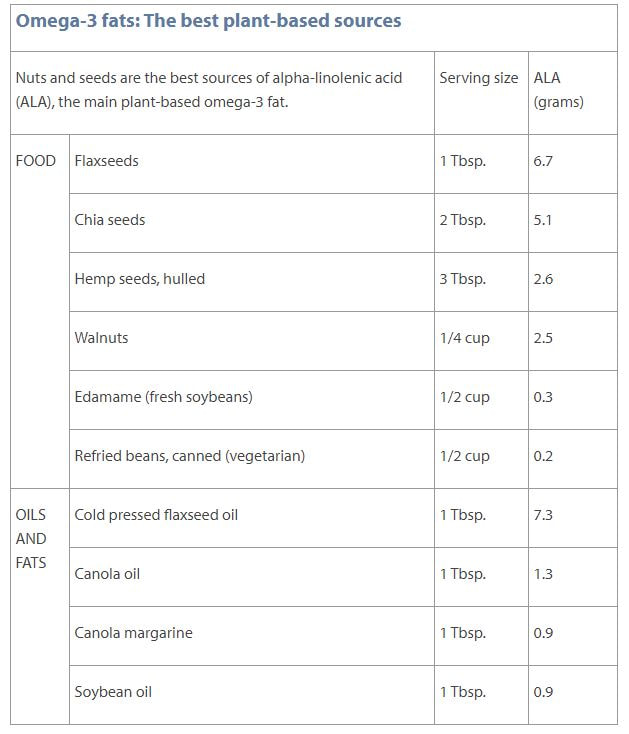

But a less-familiar form of these unique fats, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), occurs only in plants and is actually fairly prevalent in some American diets (see "Omega-3 fats: The best plant-based sources"). Now, a new study suggests that higher blood levels of both fish- and plant-based omega-3s help lower the odds of a poor prognosis in the years following a heart attack.

Differing benefits

"It's an intriguing study and clearly in line with what you'd expect to find," says Dr. Eric Rimm, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. For the study, researchers measured the serum blood levels of EPA and ALA in nearly 950 people hospitalized for a heart attack. The serum levels reflected the amounts of foods rich in omega-3s the study participants had eaten in recent weeks — a measure considered more reliable than diet surveys.

Over the following three years, people with higher serum EPA levels were less likely to have serious cardiovascular problems and to return to the hospital. At the same time, those with higher ALA levels were less likely to die from any cause. The study was published Nov. 3, 2020, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Fish findings

Earlier research has found that fish eaters are less likely than people who don't eat fish to have a heart attack or unstable angina (unexpected chest pain that usually happens at rest). One reason may stem from the cardiovascular benefits of the EPA and DHA fats found in fish, which appear to ease inflammation, prevent the formation of blood clots, and reduce levels of triglycerides (the most common type of fat-carrying particle in the bloodstream). Another possible explanation: people who eat fish may be eating corresponding less red meat or processed meat such as bacon, ham, or sausage, which contain unhealthy saturated fats (and potentially a lot of salt).

Just one salmon dinner and a tuna sandwich for one lunch over the course of a week is enough to meet the American Heart Association's recommendation to eat two weekly servings of fish. (A serving is 3.5 ounces, or about 3/4 cup of flaked fish.)

Plant-based alternatives

But what about people who don't eat fish, either because they are vegetarian or vegan, or because they simply don't like it? Your body can convert plant-based ALA to EPA and DHA, although the efficiency (called the conversion rate) appears to vary quite a bit. Among people who don't consume fish, there appears to be increased expression of the genes that create the enzymes that transform ALA to EPA and DHA, says Dr. Rimm. Genetic differences — which may reflect geographic differences and therefore food availability — may also play a role.

What's more, people can get about 10 times as much ALA in their diets as EPA and DHA, which may help compensate for a low conversion rate. Most nutrition-conscious vegetarians get ALA from a diet rich in nuts and seeds, especially walnuts, chia seeds, and flaxseeds. But soybean and canola oil also contain ALA. These oils are popular for cooking, and they're also found in salad dressings and margarine, as well as breads, crackers, cakes, and cookies.

The bottom line: Include fish in your diet if you enjoy it. But following a healthy vegetarian or vegan diet — including whole or minimally processed foods that are rich in ALA — is probably just as beneficial for your heart.

www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/omega-3-fats-and-your-heart

Since the late 1970s, hundreds of studies have supported a link between omega-3 fatty acids in the diet and a lower rate of heart attacks and related problems. The best-known omega-3s — found mainly in fatty fish such as salmon, herring, and mackerel — are eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

But a less-familiar form of these unique fats, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), occurs only in plants and is actually fairly prevalent in some American diets (see "Omega-3 fats: The best plant-based sources"). Now, a new study suggests that higher blood levels of both fish- and plant-based omega-3s help lower the odds of a poor prognosis in the years following a heart attack.

Differing benefits

"It's an intriguing study and clearly in line with what you'd expect to find," says Dr. Eric Rimm, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. For the study, researchers measured the serum blood levels of EPA and ALA in nearly 950 people hospitalized for a heart attack. The serum levels reflected the amounts of foods rich in omega-3s the study participants had eaten in recent weeks — a measure considered more reliable than diet surveys.

Over the following three years, people with higher serum EPA levels were less likely to have serious cardiovascular problems and to return to the hospital. At the same time, those with higher ALA levels were less likely to die from any cause. The study was published Nov. 3, 2020, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Fish findings

Earlier research has found that fish eaters are less likely than people who don't eat fish to have a heart attack or unstable angina (unexpected chest pain that usually happens at rest). One reason may stem from the cardiovascular benefits of the EPA and DHA fats found in fish, which appear to ease inflammation, prevent the formation of blood clots, and reduce levels of triglycerides (the most common type of fat-carrying particle in the bloodstream). Another possible explanation: people who eat fish may be eating corresponding less red meat or processed meat such as bacon, ham, or sausage, which contain unhealthy saturated fats (and potentially a lot of salt).

Just one salmon dinner and a tuna sandwich for one lunch over the course of a week is enough to meet the American Heart Association's recommendation to eat two weekly servings of fish. (A serving is 3.5 ounces, or about 3/4 cup of flaked fish.)

Plant-based alternatives

But what about people who don't eat fish, either because they are vegetarian or vegan, or because they simply don't like it? Your body can convert plant-based ALA to EPA and DHA, although the efficiency (called the conversion rate) appears to vary quite a bit. Among people who don't consume fish, there appears to be increased expression of the genes that create the enzymes that transform ALA to EPA and DHA, says Dr. Rimm. Genetic differences — which may reflect geographic differences and therefore food availability — may also play a role.

What's more, people can get about 10 times as much ALA in their diets as EPA and DHA, which may help compensate for a low conversion rate. Most nutrition-conscious vegetarians get ALA from a diet rich in nuts and seeds, especially walnuts, chia seeds, and flaxseeds. But soybean and canola oil also contain ALA. These oils are popular for cooking, and they're also found in salad dressings and margarine, as well as breads, crackers, cakes, and cookies.

The bottom line: Include fish in your diet if you enjoy it. But following a healthy vegetarian or vegan diet — including whole or minimally processed foods that are rich in ALA — is probably just as beneficial for your heart.

www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/omega-3-fats-and-your-heart